How to write hits

Giving up on trends, clawing towards truth, & four Atwoodian rules for greatness.

You sit there, on your 4th or 5th half-drunk seltzer of the day, brow furrowed at the awkward thinkpiece you cobbled together, regarding the Sanchez/Bezos wedding.

You’re at 9%.

I don’t mean your phone battery.

You’re buffering. You want to write something of consequence. Something of value.

You want to write with the substantive weight of Steinbeck, except this viral moment caught your eye. So instead of waxing poetic about the Joads, you’re chasing a trend about the Bezoses and now your brain feels like one of those playground roundabouts — endlessly looping until a kid’s shoe or football or Hello Kitty backpack gets lodged underneath it. And even then, still, endlessly, it loops. But now with an additional rhythmic speed bump, every two seconds, cracking your jaw against the bar to which you cling in an attempt to fight centrifugal force.

It’s at this jaw-debilitating crossroads that you consider: do I just pull the trigger on AI? Put a few finishing touches on a computer-generated take and call it a day? Is it really worth it to think this hard?

The moral judiciary in you might say things like, Of course you should THINK. It’s the human thing to do! Be a human! Boooo AI! Trends are BS! Write something wildly important, you twit!

But the practical day laborer in you might say things like, When I throw my life force behind an essay that gets little more than crickets, why oh why, would I waste time on THINKING when I could lay flat on the ground and stare up at my ceiling fan instead? Just pick a trend and plug it in, idiot.

Tale as old as time: You’re caught between the easy way and the hard way.

Choosing is not so simple.

The hard way (thinking) doesn’t always yield results.

The easy way (AI-using, trend-hopping, virality-chasing) doesn’t always yield results either, but at least you aren’t wasting your time and your effort on it. At least you’re not exhausting your already bone-tired-by-capitalism pretty little head.

And you know what? I get it.

I get why an independent working class artist like yourself would doubt the power of your own thinking. I get why you would judge your ideas against the potential of their network effects. I get why you’d quit writing or making or doing anything at all.

And I do not judge.

But I came here to tell you something no one in the ruling class wants you to know. It’s a tactic to make your art a powerful, contending force.

It’s something slippery, hard to catch. Almost like luck. And yet, it has the staying power of a 2-year old gripping the empty pantry door, screaming “Elmo bar!” when he knows for sure, they are ALL DONE, and yet he shall not be moved for anything, not snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night.

The tactic is this: tell the truth.

I see your eyes have rolled to the back quadrant of your brain.

Before they get stuck there, and you click back to your draft about the Bloom/Perry uncoupling, let me tell you…

Telling the truth is not a cute “authentic” moment.

Telling the truth generally feels like getting your eyelashes ripped out one by one. Or getting a Brazilian. Or getting punched in the face by the angry, Elmo bar-less toddler.

Telling the truth is not nice.

But it is necessary.

And before you accuse me of selling a fantasy, allow me to also clarify: I don’t think every time you tell the truth you’ll write like Steinbeck. Or your film will get picked up in the mainstream. Or you’ll always have a hit.

I also don’t believe simply telling the truth is a panacea for the material discontent working class artists like us feel every single day.

It’s just that telling the truth is the only way to even approach greatness.

And here’s more bad news!

You can’t just, like, do it once and then feel good about it. Telling the truth in your work is not a milestone. It’s an exercise. One you have to keep repeating.

Your potential atrophies without the reps.

Truth is Super Annoying

Truth is annoying to consider1 because even if we objectively agree on what constitutes truth:

perhaps the feeling of aliveness?

ummm the presence of nuance?

maybe something that makes us laugh?

Even if we agree on all of that and in summation we have what we call CHARACTERISTICS OF TRUTH… doesn’t it still feel a bit nebulous? A little spongy? Hard to hold?

Personally, I find it all very cumbersome.

So I’m calling in a professional and seeing how we can take the concept of truth, and make it less like little grains of sand and more like a sand castle — still hard to carry, but at least we’ll have something to kick.

The Atwoodian Truth-Telling Rules (as I see them) and Why They Work

In 1983, Margaret Atwood2 gave a speech at University of Toronto’s convocation. It’s one that could be given today without many edits because it tells the truth.

Not only is she telling the truth about her experience of the post-college world, she’s telling the truth about her experience of writing the convocation speech itself.

I beg you to read the whole thing here. What a delight.

Below is a 4-point list of examples from within the speech to help elucidate the concept of truth, how it’s used, and why it works.

1. The process provides.

One infallible rule of writing: when you don’t know how to start, pay attention to your own process and tell the truth about what’s happening with you.

In her speech, Atwood lists all the discarded ideas she had for the speech. Perhaps she didn’t think she could stretch a tight ten out of one idea, so she zip-tied them all together instead. Perhaps presenting her thinking process was a self-conscious tic. Perhaps the rhythm just sounded right to her.

Why she chose to include all the discarded ideas within her speech doesn’t really matter. What matters instead is the feeling of truth we get from it.

She starts the meat of her speech, five separate paragraphs, in these ways:

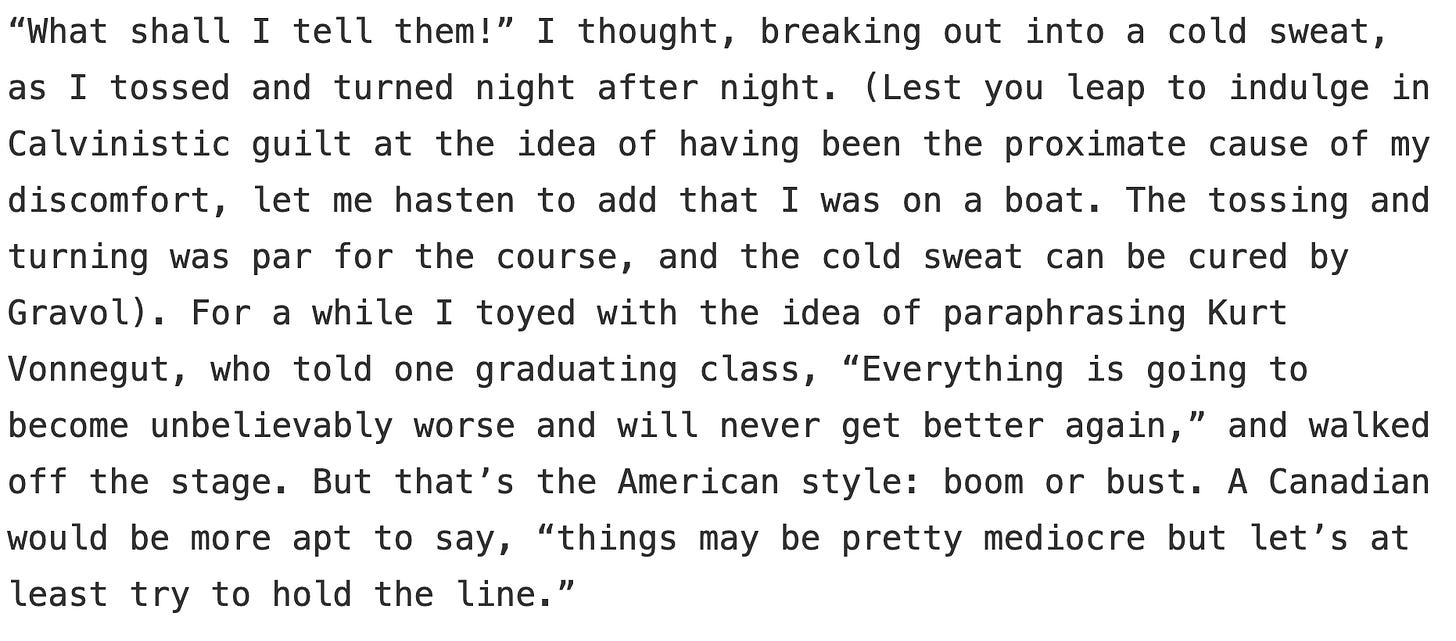

“‘What shall I tell them!’ I thought, breaking out into a cold sweat, as I tossed and turned night after night.”

“Then I thought that maybe I could say a few words on…”

“Or maybe, I thought, I should expose…”

“But I then thought, I shouldn’t talk about writing…”

“Or maybe, I thought, I should relate to them a little known fact of shocking import…”

Why does this feel like truth? Because what do you say to a group of college-aged kids crossing the cozy academia to brutal life threshold? There’s actually nothing you could say that would give them any answers. Because they will never have the answers. Only questions. Confusions. A bunch of ideas they’re going to have to zip-tie together for themselves sooner or later.

She could have given them platitudes. Great “truths” AI could scrape off of brainquotes.com for us to print on fridge magnets. Why didn’t she use her skill to twist these ideas into easily digestible turns of phrase, making her seem very smart and dignified?

Because she know better. She shows, instead of tells.

In showing her speechwriting process, Atwood is echoing a truth to the students: you, also, will have to struggle with some cold night sweats before you figure out what to do with your life.

The power of the speech resides in the fact that she demonstrates that struggle.

So here’s the Atwoodian trick: when you’re awfully stuck and not sure what to say, look at your own process and you may find clues for a way in.

In other words, write about what’s currently happening to you, the writer, to know what to say to them, the audience.

Don’t make it tidy. Make it visible.

2. Say it small.

The most effective parts of the speech aren’t the sweeping statements about how the graduating class will get on in the world. The most effective parts are quite small. They are so specific that a lesser writer might consider them too specific.

But really great writers use actual brand names whenever possible.

Here’s the section I’m talking about:

She could have stopped at “tossed and turned night after night” and it would have been a fine cliche, but she didn’t. She specified.

One of the best lines is: “let me hasten to add that I was on a boat.” And then she specifies even further, “the cold sweat can be cured by Gravol.”)

It’s the specifics.

She allows herself the cliche because it sets up our expectations. We’d accept it if she stopped right there. But when she doesn’t, when she specifies further, the cliche gets embedded with all new power. We see her, on a boat, popping Gravol.

And here’s the thing about the truth — it doesn’t need to be real.

Maybe she was on a boat, maybe not. But the image we get of her tossing and turning on a boat, chewing anti-nausea OTC meds gives us the truth of how it feels to be her writing this speech.

Specifics’ll do that.

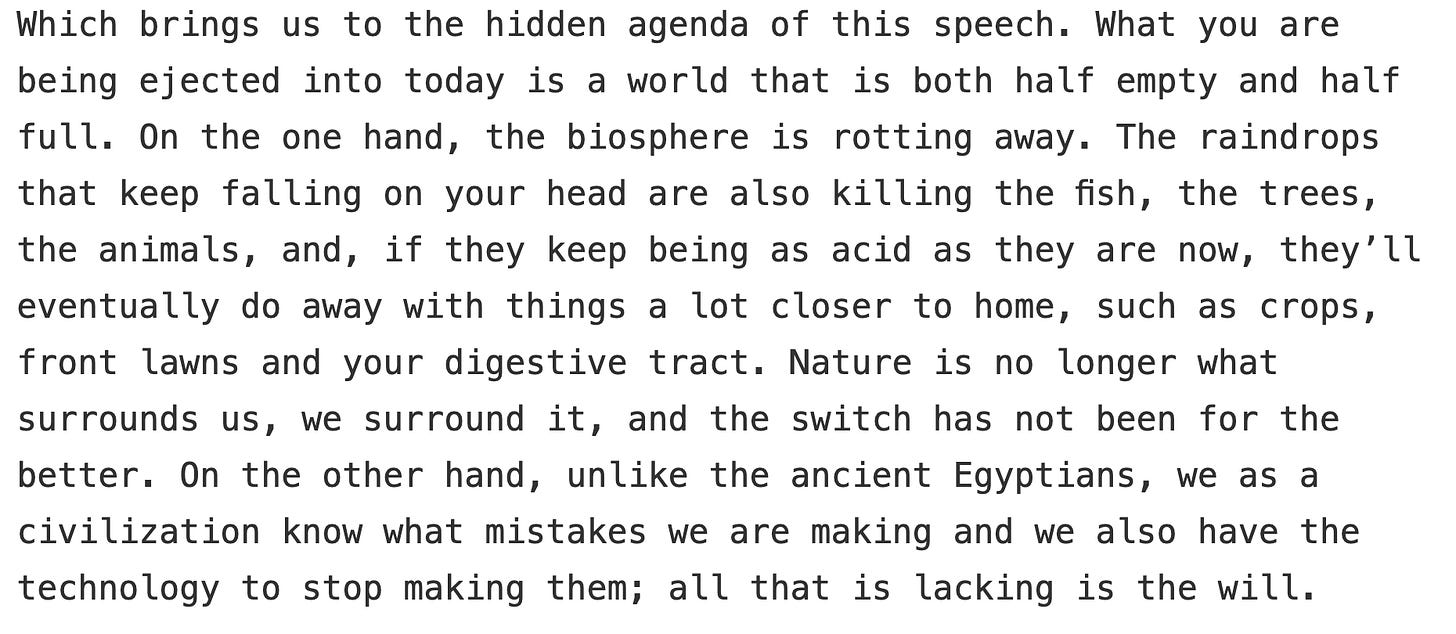

3. Don’t rest on one side.

If you’re hellbent on telling the truth, there will be no easy conclusion you can draw.

As soon as you argue from one position, another (better, different, stronger) position will reveal itself to you just before you hit publish.

Atwood makes this opposing force the central component of what she has to say:

Why does this work? Let’s think…

Ever see a midnight infomercial for reusable paper towels that promises to transform your everyday cleaning routine into a thrill fest?

Ever hear a politician call a protest a riot?

Ever meet a 6-year old who swears if you just let her watch one more episode of Bluey she’ll absolutely go brush her teeth for 120 seconds like the dentist recommends and then get right into bed without a fuss?

Right. It’s all propaganda.

And our brains, when thinking, know when we’re being conned. So when a writer or another kind of artist comes out and says the truth out loud: “IT’S MOST LIKELY BOTH/AND AND WE’RE GOING TO TRY AND MAKE THE BEST OF IT BUT MAYBE ALSO WE CAN’T” — we can feel that truth down to the bone.

4. Enter the doorway and walk all the way in.

Finally, Atwood does what I believe all great artists do. She doesn’t shirk the responsibility of her setups.

If she opens the door to an idea, even if it’s a tangent, she walks into the room, looks around, finds a nice comfy recliner by the window, pulls it up just close enough to feel the breeze, flops down into it, lifts her feet to the windowsill, and stays awhile.

Here’s what I mean:

She starts with her setup: nobody ever tells you, but did you know that when you have a baby your hair falls out?

She goes on to explain how much hair falls out, and when, and due to what, and that it’ll turn out okay (for girls). Then she goes even further to discuss another case study about how it won’t turn out okay (for boys). Then she goes even further to offer a tidy little quote, when all else fails.

Why does she go so far? Why doesn’t she just stop at the setup?

Because part of telling the truth isn’t telling anything. It’s simply showing how you think. It’s exposing yourself. Allowing yourself to follow the rhythm or whim or kick you feel like following.

Telling the truth isn’t about imparting ideas unto your audience.

It’s about imparting you.

Here’s the Only Thing I Can Guarantee

Look, can I confirm that if you follow these plucky little rules you’ll turn into the modern Margaret Atwood and change the culture in such a way that we all wake up and realize the truth? Of course not.

Can I confirm if you follow these rules you’ll even be a better writer? Not really.

All I can confirm is that by using these rules, you’ll find yourself idling up to truth in a way you haven’t before. You’ll get close to it, peripherally, like it’s a gorgeous stranger alone at the bar and you just happen upon this barstool right here.

After awhile, you may end up looking truth in the face. And that will be its own seductive reckoning.

But even if you don’t — you’ll soon realize that the sheer act of trying, of simply pulling up a seat, and brushing shoulders with something as irresistible as truth, is in fact, all you need to have a really great night.

This is the third post in a series considering the concept of rigorous thinking and how independent artists can leverage it to gain more power.

Rigorous Thinking Series:

The Revolutionary Rigor of Working Class Independent Artists

How to Outperform "Second Screen" Content & Find Your Audience

The Free Thinking, Coalition Building, Truth Insisting, 21st-Century Artist

Tell me in the comments: Which Atwoodian “rule” is most/least appealing to you?

Besides making movies and writing, I help other folks with writing and indie infrastructure.

Tell me what you’re working on and let’s hop on a short development call. (FREE)

Get The Writing Process Stack to resurrect your Untitled stream of consciousness drafts from your Trash folder and start using your forte voce.

Take the Artist Timeline Quiz, which is honestly just a lot of fun. Folks often take it multiple times as a sort of quarterly calibration. (FREE)

And I do apologize for forcing the consideration.

I’m sure you know her already, but diligence must be due — she wrote The Handmaid’s Tale, Oryx & Crake, among countless dystopian others.

It's this part for me:

Because part of telling the truth isn’t telling anything. It’s simply showing how you think. It’s exposing yourself. Allowing yourself to follow the rhythm or whim or kick you feel like following.

Telling the truth isn’t about imparting ideas unto your audience.

It’s about imparting you.

Have I not been showing my audience who I am yet? Mind blown.

this is so so so good