What makes something resonate?

001 Subliminal Signals || The opening image, gut reactions, invisible symbolism, and a close read of Jurassic Park.

My first love communicated by beeps.

A variety of beeps.

The ding of an AOL Instant Message he’d send me would send me.

His jarbled screen name, an acronym commemorating a friend who had passed, would pop up on my Buddy List alerting me he had made it through the scrawrbly diiiiing duh duh ding ding of the modem and made it online and I would count the seconds until the initiatory beep corresponding with his flawless set of salutations:

sup

or

whaddup

or

…

The ellipses were the IM equivalent of James Dean looking out from under his brow in Rebel Without a Cause. A disastrous look for any young girl.

Undid me every time.

How does one artfully respond to a … after all?

Sometimes the Love of My High School Life would beep at me from his Jetta.

He’d pull into my cul-de-sac in a red hatchback, give me a quick beep-beep as if to say, Let us not dilly-dally, and I’d descend from my house into shotgun knowing the thrill of what was about to unfold: hanging in some basement decked in black lights and lava lamps, where we would talk and hold hands, and I would feel as if the entire universe revolved around his every word to me.

Granted, those every words were very few words, but they each meant something.

Those words were a code, a symbol I would only understand if I truly understood him.

Sometimes those words were numbers: 4655

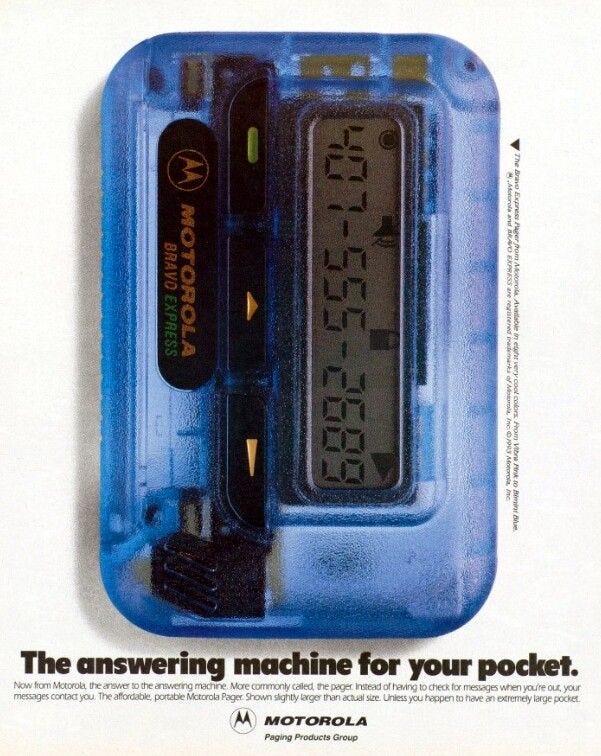

My hot pink Motorola pager would beep and the last four digits of his phone number would appear on the tiny backlit screen.

Those numbers, also, sent me.

They meant to call him. To talk to him directly and exist in his world.

Who knew what kind of mood he’d be in on the other side of the call, brooding or aggravated or amused, but it didn’t really matter because the point was: he wanted me to call.

The beeping, in its various forms, was always his opener.

Always the way he got my attention.

As you can imagine, we broke up a lot.

And during one of those longer stints of breaking up,

long before he found me that one last time before college and gave me the book The Invitation and visited me on campus, before I realized he was indeed simultaneously dating someone at home, and not only that, but so committed that he put her nickname (TLee) in the “Marital Status” box of his AIM profile, causing me to feel as if I had fever-dreamed the whole entanglement,

during one of those various breakups,

I did date someone else.

This boy was a filmmaker and a musician. An artist. He was probably a lot closer to James Dean than my fantasy of James Dean.

He told me he liked my foibles.

At 16, he was using the word foibles.

This also sent me, but in a totally different direction. Perhaps to a place where I could see myself a little bit better.

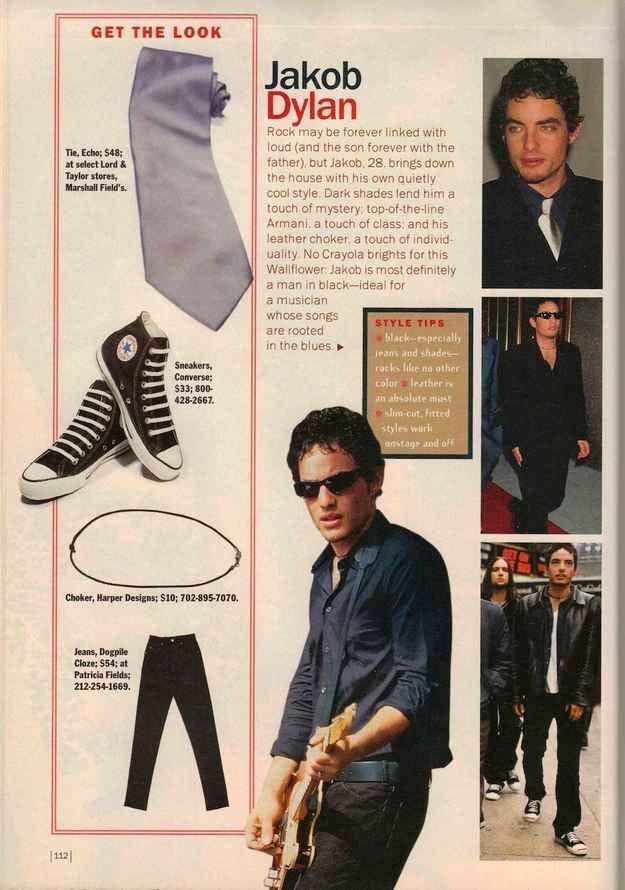

He wrote music that sounded like Bob Dylan, and he looked like Jakob Dylan. This was right around the time The Wallflowers released One Headlight, so you can imagine how pleasing this all was.

He took me out on real dates to cafes, not to basements.

I remember ordering a salad at one of these cafes — something I never ordered — and it was so large that the lettuce kept falling off my plate. Ashamed, I would pick up the awkward chops of romaine, valiantly recreating the vegetal mound in the hopes he didn’t see how new the concept of a fork was to me.

On one of those dates he took me to the movies.

I remember he was driving an old mini-van, where the seats didn’t feel fully attached, like in some alternate life this mini-van had housed the most intractable toddlers bouncing around the car, and the weary mother, beaten down to within an inch of her soul leaving her body, had more than once shrieked: NOT. WHILE I’M. DRIVING.

The mini-van was not the same as the red Jetta.

But it could haul ass.

And I remember my Jakob Dylan date hauling ass in this ancient duct-taped together mini-van to get to the movie on time. And as we walked into a hushed theater, whose patrons had just sat through the previews and were now, having finished 53% of their large buttered popcorns, ready for the main event, we quickly snagged a couple of seats dead center down front, and he said to me with a sweet smile on his face:

“I can never miss the opening of a movie. Otherwise, I feel like I’ve missed the whole thing.”

And, Dear Reader, in that instant, I was fully transformed.

Partially because he said it so kindly, almost apologetically, to me. (He wasn’t rushing me, he just had this thing.)

Partially because I had a suspicion that what he was saying had some deeper, more profound cinematic truth and I wondered how he, a 16-year old boy from Central Pennsylvania, got ahold of such a truth.

And partially because I had no idea what he was talking about.

There was, of course, the entire rest of the movie? What did he mean by missed it? What about the plot? There was no plot in that opening image. The PG-13 fare of the early 2000s typically just used a wide establishing shot for the opening image. (Not that I knew what a wide establishing shot (or an opening image) was.)

I spent the first half of that movie, repeating his words over and over in my head, trying to figure out what they meant. I was so fixated on his philosophical Rubik’s Cube that I did actually miss the opening image.

I don’t remember what we saw.

But I remembered what he said and how he said it. And as I grew older, and got some more of the reds on one side and all the yellows on the other (that is to say: started understanding what he meant), it has now become very personal to me.

If my gorgeous husband talks during the opening of a movie, I turn to him, wonderful and patient man that he is, and say, “Babe! Shh! I can’t miss the opening!! I’ll miss the whole thing!!!”

The Invisible Symbolism of the First Frame

Whether you’re a filmmaker or not, your opening image is, indeed, everything.

From marketing copy to your memoir, your opening doesn’t just set the tone. It asks the question the rest of your writing will try to answer.

When I was 15, I thought the opening image didn’t contain any plot. And in some ways that was right. It doesn’t contain plot, it contains the whole movie.

It’s like the roundness of eternal time — everything from the past and future conjoin into one gloriously rich present moment and if you’re attentive enough, everything you could feel or know or suspect is right there, in that one image.

No pressure.

While the majority of my first draft gets ripped apart over the process of 248 subsequent drafts, the core feeling of my first imagined opening image tends to more or less end up on screen. Because when I write, I allow my intuition to begin the process.

I see a fleeting symbol or hear a random bit of dialogue and write it from gut, which jumpstarts the entire story. I’ve tried to plot things out before, make logical choices about who and what and where should be shown to elicit the appropriate feelings and dictate the appropriate theme, but the truth is I get very bored if things have too much perspicuity.

(Lest you forget, I was in a love with a boy who communicated via ellipses.)

And this is what I think makes a good opening image anyway: Just enough information to orient us to where we are, but just little enough to make us lean in.

A good opening image will turn on my brain like a radio looking for a signal. Because I know if I’m tuned in, the opening image is going to capture some essential wholeness of the movie.

Then, things really get fun:

It will have me leaned in, trying to get ahead of it, and yet somehow inconspicuously sweep me into the story, giving my head a rest and putting my body (with its assorted guts, instincts, and deeply hidden emotional truths) in charge of watching.

The Wacky, Subliminal Dance Between What We See First & What We See Last

So now we have to talk about the closing image.

It does more than tell us where the story ends. If it’s good, if it’s really, really good, it’ll be a satisfying counterpoint to the opening image.

I don’t mean it’ll put all the pieces together and there won’t be any mystery left. Actually, a good closing image will increase the mystery a touch.

It’s satisfying because of what’s missing. Like two puzzle pieces worn down over time with the paint picked off, the opening and closing image connect but they leave just enough room in your imagination to fill in the gaps.

It’s that “just enough” connection that forces the human mind to make meaning.

And when we make meaning out of something, it becomes ours.

This is a profound thing.

Filmmakers and writers are offering more than “how the story starts” in the opening image. And they’re offering more than “how the story ends” in the closing image.

They’re offering the audience an opportunity to make of it all what they will.

A chance to look at this 90-minute phantasmagoria called a movie and play God for a moment and decide the truth.

The entire movie, beginning with the opening image, revs the audience’s interior energy. It keeps layering on information with turns and surprises and heartaches and longings until finally we have to know what happens in the end.

When we get to the final visual, which cost thousands of dollars, hundreds of hours, and 10-12 heated arguments at minimum to make, we know it’s on purpose.

And we, the audience, are left alone with it.

The reins unceremoniously handed over to us each time.

Sitting with the credits, trying to figure out what we just saw.

When that lingering moment of meaning-making brings us back to the opening image, not to satisfy our need for someone to “just tell us what it meant”, but in a formative, rich way that offers us the deep pleasure of believing our own intuition and feeling at home in what our own bodies know,

the movie becomes nothing short of magic.

A Close-Read of How Jurassic Park Builds Resonance Between Images

Even as the movie freak I am, sometimes I don’t even notice the magic as it happens. Even movies I’ve fully dissected and put back together can still whip me into a magical frenzy.

One of those movies for me, which I’ve watched at least 36 times, is Jurassic Park.

The scene with the flipped over Jeep and the eye of T. Rex? Flawless.

The Goldblumian Philosophy of chaos? Impeccable.

Laura Dern as a general rule? No notes!

But the thing that still gets me the most is that final image and the unconscious yet airtight connection it makes to the opening image. So let’s start there.

ASK: What do we see first?

Spielberg gives us an opening image that tells us everything and nothing. (Again, the roundness of eternal time, etc.)

At first it looks like a tree shaking. Or perhaps a bush. It’s dark out, there’s a splash of light on what looks like leaves. But I’m not altogether sure if it’s actual leaves or fake plants. It’s hard to tell. As the leaves rattle, we see they’re rattling against something. A body? Or no, is that a car? Chainlink?

We linger there just long enough, in the dark, barely able to see why these leaves are shaking before we cut to to the next image: a worker’s face, on high alert, his breath tightly held, his jaw set and immovable. He watches what we’re watching:

Those damn shaking leaves.

We don’t know what’s behind them, but we can guess. After all, we came to see Jurassic Park. It’s probably dinos.

But still, we aren’t sure what the combination of shaking leaves, the man’s set jaw, and the darkness is all going to mean.

And then, a cage emerges.

The cage was the thing shaking the leaves. The cage is the reason there’s a worker. The cage is the opening image of the story.

And the story is about what’s inside it.

ASK: What do we see last?

Spoilers ahead! (Just in case!)

You know what happens in the film, dinos! chases! quippy one-liners! So let’s now jump to the final image.

Dr. Alan Grant (Sam Neill in all his grandeur) sits freshly traumatized (but also freshly saved) in a helicopter flying away from the park. He opens his eyes from sleep to see Dr. Ellie Satler (the perfect Laura Dern). She smiles at him, as the two kids (the same ones he tried to shake off him at the beginning of the movie) rest easy in his arms.

Let’s pause here to ask: if the film ends on that image, what would it mean?

Would it mean Spielberg believes kids are the ultimate progression of life? Would it mean a man can change? Would it mean that nothing is more important, when you’re brought to the brink of death, than your relationship with the next generation?

It might. But then, what about that opening image? The rattling leaves? The shaking cage?

That ending doesn’t quite track back so elegantly, does it?

So Spielberg (being Spielberg) knows we need another image.

One more final image that is going to bring the story to its full weight.

And that’s when something catches Dr. Satler’s eye. She looks out the window. Dr. Grant notices this and follows her gaze.

We watch him watching, and then we see for ourselves:

Birds.

Out the side of the helicopter window, a flock of birds fly across the ocean. Wild birds. Free birds. Uncaged, if you will.

We cut back to Dr. Grant, who has been arguing the whole movie, and in the hints of his backstory, that birds evolved from dinosaurs. He rests his head back against the wall in a sort of surrender and awe, having just personally witnessed millions of years of evolution from the ground to the sky.

Off Grant’s smile, the music swells and we cut back to now just one bird. One bird flying towards a setting sun. That, presumably would be quite a lovely final image. The dinosaurs freed themselves from both the cage of Jurassic Park and the cage of evolution. As Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum) says: Life finds a way.

But we’re actually not there at the end yet, are we?

It’s one thing to see the bird flying free — a clean and perfect counterpoint for the opening image of the cage. With only that, perhaps the moral is: let’s actually not try to control the animal kingdom, k?

But caged bird / uncaged bird is too tidy. It’s a little on the nose to end there, is it not? And that may be why it’s not the final thing we see.

The last thing we see after the bird flying toward the horizon is the helicopter flying towards the horizon.

The birds are free, but so are the people in the helicopter. They’re free of the dinosaurs, yes, but they’re also free of something more — the illusion they can control life or bend it to their will.

And it’s in that humbling of themselves to the power of life, they may just live to see another day.

This final image, of the freed helicopter flying into the distance, mirroring the birds, extracting a second meaning of the Goldblumian life finds a way, is made possible by that first cage.

It has more depth because of it.

Even when I just watch the scenes and skip the whole middle part (you know… the movie), I feel a visceral reaction to both the opening and the final images.

And that’s partly because I remember what it felt like to see that final image for the first time. It was striking, and moved my unconscious mind. The movie added up to this.

How Gut Feeling Creates Resonance

When I watched Jurassic Park for the first time, I was confronted with themes of captivity and freedom.

I could lie to you and say that, at nine years old, I saw the movie as a message about the “futility of trying to control life and it being better to just let it run wild and watch in wonder and amazement for as long as you can including, by the way, how you, yourself, as a grown adult, may want to be free of kids as a rule, but having confronted that principle more deeply, you discover that life finds a way in you too, and you feel the biological pull towards caring about children (if not rearing them yourself) because children do indeed perpetuate life, which, again, will find a way, even for us humans.”

But that’s not what I was thinking.

I was making visceral connections. I experienced, within my body, an alchemy from that combination of images, free from words.

What I felt was a kind of resonant satisfaction.

At nine years old, I was both glad they escaped and kind of bothered by it. I was unsettled by the fact the dinos were roaming around, uncaged.1

It was scary to me to think that life would continue to find a way without the control of the adults in the room. There were no adults in the room anymore, after all. They were flying away in a helicopter towards a damned sunset!

Flying into the distance (no matter how pleasantly Sam Neill smiled) felt, to me, like a half measure. Like, um, okay, sure… everything was okay… for now.

But how could they be so sure of themselves? How could they be so relaxed? The T. Rex was still out there!

Which is a lot like how life is.

Knowing there may be (metaphorically speaking) a resurrected dinosaur population evolving its way to a sequel of unfortunate events in our own lives, we hold onto whatever we can while we can: sleeping in the curve of someone’s shoulder, or the setting sun, or a flock of birds.

It’s not lost on me that when I saw this in theaters, I was holding onto my dad’s arm through the whole film, jumping with terrified delight, my dad giggling at my squeals and patting my hand saying it’s alright. And the feeling that, because he said so, it was.

A movie can become resonant because of so many tiny moments like that. Most moments we, as filmmakers, will never know.

The invisible traces of our audience’s lives will, as they watch, connect and spark with the tiny signals we place in this frame or that one.

We can never know what they’ll all add up to.

All we can do is offer the invisible traces from our own lives, our own significance and meaning, and hope our side of the puzzle connects with theirs.

Practical Application: How to Devise an Inventive & Resonant Opening Image

An opening image will grab attention, hold it, and make the audience’s experience a visceral one.

The underlying principle of a good opening image applies to beyond just film. It includes the words you use to begin a story of any kind.

So let’s take something you’ve already written. It could be a scene or a whole movie or a short story or an email. The format doesn’t matter for this exercise.